August17, 2002

Dear Villagers,

I had a most enjoyable and enlightening trip to Japan which included visiting five homeless camps (four organized) in Tokyo and Osaka, and observing several others from a distance in Kyoto and Hiroshima (small in number). I'm including most of the photos - not entirely great photos - but some good memories. If I can find my notes, I do have names for some of them, but here they are in the meantime. Everyone in Japan will be looking to find themselves on the Dignity Web site! The photos are:

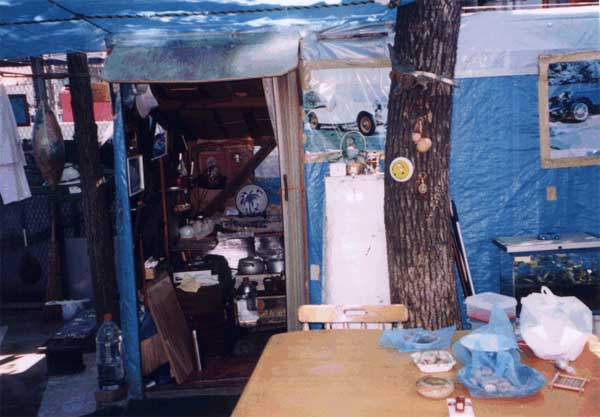

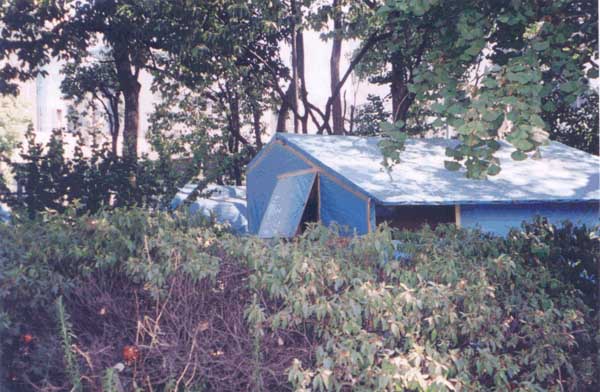

a) My visit to Ougimachi Park Tent Village in Osaka (August 6th) having about 30-50 tents.

b) My visit, the same day, to Nagai Park Tent Village in Osaka, now down to about 15-20 tents.

c) My visit to two tent villages in Tokyo, the first of which is located at Shibuya Miyashita Park and the village there was called Ryosampaku which means 'center of the park.' In Ryosampaku proper there are 15-20 tents but in the park as a whole there are about 100 people and 80 or so tents. We then went to another tent village called 'Yoyogi Park' (which was at this park) which has about 300 tents. It is a large park and is very popular with the young people on the weekends (and summer holidays, like when we were there - street bands, many vendors along the sidewalks, lots of life and activity nearby the park or along side the park).

My guide for Osaka was a long-time supporter called Tabirounin and another supporter who served as the translator at Ougimachi called Yamamoto-san. There are only two organized tent cities in Osaka, but many many small scattered tent groups in various parks there, mostly unorganized and without formal methods of communicating with one another (although I'm sure they do communicate). Both Ougimachi and Nagai have separate supporter groups that assist these tent communities.

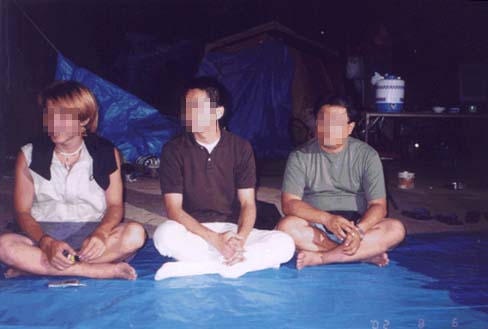

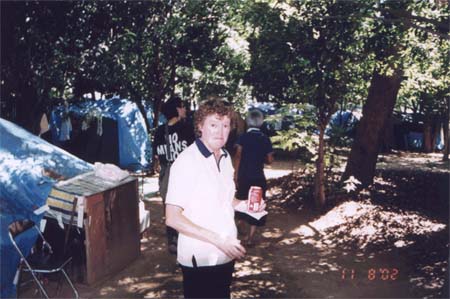

Supporter Linda Neel, Yogogi Park

My guides in Tokyo were Yamamoto-san and Rayna Rusenko, an American working in Tokyo who is fluent in Japanese and a member of Nojiren, which is a sort of private name for what really is the 'Shibuya Free Association for the Right to Housing and Well-Being of the Homeless'. Initially, from the use of Nojiren I had thought it a person's name and, indeed, some articles appear to be written by 'Nojiren'.

The situations in Osaka and Tokyo seem to be quite different. First of all, let me mention that my impressions of homelessness in Japan may be very inaccurate, obtained from some web sites and information that I read while there and from talking with the supporters and homeless. Sometimes there were challenges involved with the translations and I have lost or mislaid a whole bunch of my notes, so everything I am writing here is from memory. So I am apologizing in advance for any inaccuracies.

From an article in late July in the 'Japan Times', it said there were (only) some 20,000 homeless in Japan (and I read other 'official' figures that state there are 30,000 homeless), with most of the homeless located in Tokyo and Osaka, which the article said had some 8,000 homeless. This article mentioned that each governmental unit (prefecture) is responsible for its homeless policies (shelters, payments to homeless, etc.) and that such policies vary considerably, being far more 'generous' in the Tokyo area and being more restrictive in the area with the greatest number of homeless, Osaka. Tokyo has some 25 million people in the area and about 13 million in the city proper. I believe Osaka, the second largest city, has about 9 million in the area. If you go strictly by the 'city' definition, then Tokyo has about 13 million, and Yokohama, at the foot of Tokyo Bay, is next in population at around 4 million or so (normally it is clumped in with Tokyo, and Osaka then is the third largest city with only about three million proper! I suppose statistics do with homeless populations much as they do with cities' population numbers, that it depends on what is included and a little of what you're trying to illustrate.

The same article mentioned that there was some limited financial support for homeless individuals, which seemed to be in the range of about $300 per month (quite a bit higher in Tokyo) but that depended on the local governmental policies and that the payments were limited in the time frame you could get the payments. As more shelters are being built (especially in Osaka), I was told that such payments are being eliminated entirely.

Yet, the homeless supporters in Osaka said there are about 20,000 homeless alone in Osaka, so my guess is that the governmental and 'official' figures are way, way low. Homelessness is growing rapidly in Japan, especially since the country is still in the midst of a 13 year recession, and companies are increasingly adopting what I think of as American techniques - layoffs, especially with their more costly 'senior' employees. It used to be, of course, that you had a strong loyalty between a company and its employees - sort of like a family, really - and lifetime employment. This has changed. Further, the family dynamics are changing which is creating all sorts of new stress in this society - an epidemic of sorts. So, the US (and other countries) is succeeding in exporting its business philosophy and some of its values or lack thereof, no doubt increased by the WTO accords. Bottom line: the homeless situation is rapidly becoming worse in Japan.

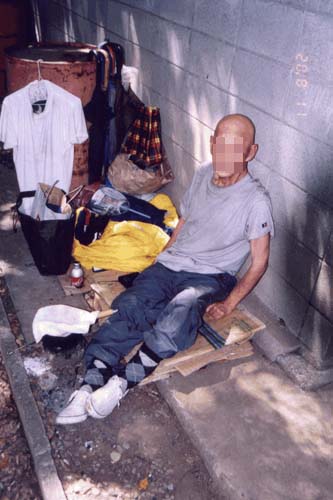

The official average age of homeless people is about age 50 there and these people have little likelihood of regaining any permanent employment - there are not the jobs and training for new jobs is inadequate, which leaves these people homeless or showing up for 'day labor' situations. These people are shamed, for they have the work ethic, want to work and now are in a homeless situation, so they stay somewhat out of sight and try not to be highly visible. Yet, as here, in my opinion, the reasons for homelessness are often structural and not the particular individual's 'fault', but rather are the "system's." And, given the changes in the family, I would expect in the future that more youth there will fall into homeless situations.

In spite of the growing homeless numbers and situation in Japan, it is very obvious that homelessness is far more severe and cruel in the United States, with an estimate of around 1,000,000 homeless (the lowest figure I've ever read is some 300,000) and possibly several million more 'on the fringe' in a country of around 300 million people, compared to Japan's 125 million people and the governmental claims of only some 20,000 homeless.

Even Mother Teresa noted, when she visited New York City, that she had never seen greater suffering than there, which is amazing considering the conditions in Calcutta and Bombay. We have a sort of go-it-alone culture and homelessness involves shame in a country that has a strong work ethic and an emphasis on materialism in all aspects of living, so homeless conditions (given our lack of a sense of 'community') results in far more misery and challenges here than in other countries where there might even be worse conditions, but where there is greater support from one homeless person to another or acceptance and support from the greater community.

In Japan, in this respect, given their culture of non-confrontation, getting along with one another, being extremely considerate and well-mannered with each other, I was told many small tent communities just didn't have any organization but that they all just got along fine with few problems or need for any supporters or formal organizational structures. All of the park tent communities I visited just functioned with little or no formal structure or organization or leadership, but people just get together regularly and everyone steps in to help where needed or if they see a void, just individually step up to fill that role. And, the supporter groups for each of these parks try to look at food needs, health needs, and just be true "supporters".

As compared with other tent groups without tied-in supporter organizations, these groups all seem to be more politically active and wanting to stand up to the police and politicians who want the tent communities to move increasingly to less-conspicuous areas or into shelters. Like here, the shelters seem to work for a certain number of homeless but don't work for others Ñ they are small, and normally you can't have pets. The shelters in Nagai Park only served one meal a day (one bowl of rice with a slice of fish on the side) and after a limited amount of time, you need to move to another "independent living" shelter that offers more job training and after a limited amount of time, you then move on (either to a job or back to the streets). The homeless supporters and individuals I talked to said that the job programs are inadequate and are just filled by bureaucrats and ineffective, so what happens is that the shelter system is like a revolving door system Ñ you move from one to the other then out on the streets again. In these parks, they vastly preferred the informal community that exists in the tents with one another to the shelters, of which there are very few in number anyway.

In the case of Nagai Park Tent Village, there is especially an interesting history which by doing a web search you can read about in much more detail. But, in summary, with the world cup being held in this park in May or June of this year (in a stadium holding probably close to 50,000 people), this park had around 500, possibly 1,000 tents around the treed periphery a couple years ago. But, the authorities did not wish this embarrassment to be seen by the world cup attendees and ordered the homeless by a to leave the park and, apparently, there were a number of sweeps. The results were by this summer that the tent community there has less than 20 tents left, populated by either strong activists or recent homeless individuals and with a strong supporter network headed up by Tabirounin, who has maintained an Internet presence since 1989, amazingly enough. To cope with the reduction of these number of tents, the authorities built all of 36 shelters at one end of the park, hidden behind a cyclone fence and having a sort of "guard house" at the entrance (keeping us curious visitors and anyone else away).

In Osaka Castle Park, where there are another around 500 tents, the authorities are building around another 50 shelter spaces and ordering the rest of the tent inhabitants to leave this popular tourist park area. So, the homeless, while tolerated and accepted along the fringes of parks and river areas to an extent unknown in the U.S., are still being subjected to the authorities breathing down their necks, police sweeps and having to make themselves less seen and visible. In Kyoto, quite a number are living singly or in very small groups along the river, 'though I understand most there are in shelters. Often in the cities outside of Tokyo, the Japanese are respectful of nature along the rivers and don't build right up to them - similarly, they leave almost all hills treed and without housing running up the sides of the hills (the housing is on the level, below the hills). Nature is revered as part of their Shinto tradition. In Portland, using a comparison, you would find the west hills area free of homes or commercial development.

The similarities and differences in homelessness between Japan and the U.S. is very interesting. Both countries have a strong work ethic, so there is a general shame in being homeless and both societies, in general, are somewhat condemning of those that are homeless- "why don't they just get a job just like the rest of us" and so forth mentality. Further, in both countries, but very well publicized in Japan, homeless have been subjected to cruel instances of violence, largely by young males in gangs - being set fire to (individuals and tents), having fireworks (popular in Japan) thrown at them, etc. Some of this violence has heightened the consciousness of the public and possibly been positive in that respect in improving various conditions. I know that in Ougimachi and Nagai parks, for instance, the supporters and homeless people conduct a once nightly tour of the area for security reasons around 10 p.m. They look for potential problems plus look for any people they are concerned about - other homeless.

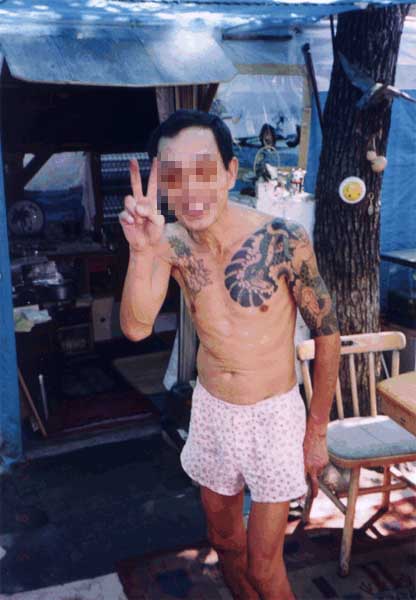

The homeless in Japan are largely (overwhelmingly) men - very few are women. Why I don't know, but suspect that most of the layoffs are men, especially older men. They do not have the same profile as homeless people in the U.S. There is not much of a drug problem in Japan so the homeless don't have these problems. You could say that crime is almost non-existent and you would be accurate. Crime is very unusual and cities are safe places as are the parks with the homeless (you will see kids and people using the parks without concern or fear of the homeless who, however, still are not in "their faces", being at the fringes of the parks under the trees, away from the main sidewalks). Further, while most Japanese like to drink (beer, sake), they don't tend to use to the point of drunkenness and there isn't the addiction to alcohol that there is in the U.S. (or so I heard).

So, while the homeless in Japan tend to be older working class males who have lost their jobs and don't have the family support or resources to be other than homeless, these groups of individuals and tents, many of which are small in number, don't have the challenges we seem to have with mental illness, drugs, alcohol as well as crime or past offenders being among the homeless. So, bottom line: our homeless have much greater obstacles and challenges, it seems to me, compared to Japan.

There are possibly more health care opportunities in Japan as compared to the U.S., but, in general, the health needs of homeless people are not being adequately met. Interestingly, if you are handicapped (wheelchair), you get an apartment in Japan and almost all wheel chairs, I saw, are mechanized. Further, if you are old, you are entitled to old age care- but in a resident home. There was one old homeless man, his name is Koizumi, that everyone helped out. He is 88 years old and just doesn't want to go to a home, preferring the lifestyle that he has. There is a huge smoking population in Japan and practically all the homeless smoke - it was uncomfortable for me in that respect and I encountered numerous people with a cough and raspy voice and it seems that they will have predictable consequences of this addiction down the line. Non-smoking places are practically non-existent.

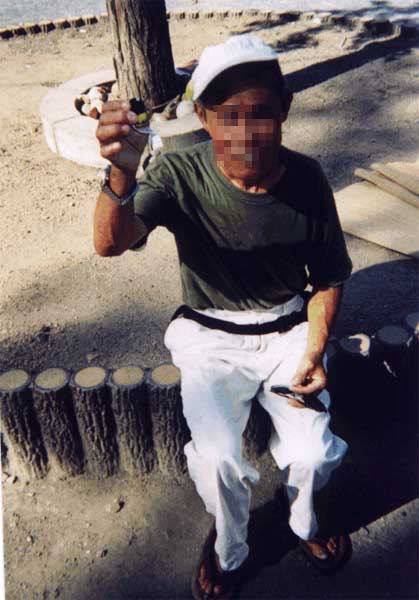

Everyone is trying to make their way. Some, as I mentioned, enjoy modest stipends from the government - not enough to use to rent an apartment, but enough to help supplement their lifestyle (usually for a temporary period however). Many homeless communities have a recycling area, mostly for cans, for which they receive about 70 yen per kilogram of weight or about one yen or one cent per can. It was explained to me that Japan, being a wealthy country, has a lot of waste and it was evident that there are far greater numbers of cans available everywhere and that this recycling can bring in relatively easy money. Further, the homeless procure thrown out book-size comic books and other books, clean them up and re-sell them. And, they have various food booths that sell sort of shish-ka-bobs and noodle dishes, etc., to the public, there not being any health department restrictions in that respect. There are, especially during the weekends, on popular sidewalks, vendors who have just found themselves a space who have found something to sell - garage-sale type items or whatever, and one of the homeless individuals - his name is Kimura (I took a photo of him) - had a space there and was selling things. These three methods are their main source of income (besides stipends and day laborer jobs). They do not seem to consider, as a community, coming up with other micro-industries like Dignity Village is doing, other than the food booths.

Our great guide in Tokyo, Rayna, mentioned that the big park we went to (Yoyogi Park) that now had 300 homeless ten years ago had only 30 homeless and she said that there are around 6,000 homeless in Tokyo. Tokyo seems pretty user friendly to the homeless compared to elsewhere and there were just lots of little groups scattered all over the city Ñ and some are worried that the City might start to clamp down on them. They don't have "soup kitchens" but there are lots of small groups that try to help out, just informal neighborhood groups, people helping people mostly. Our guide mentioned that it is rare to find young homeless people like here, for it is relatively easy to earn enough money for them to get by, unlike the older homeless individuals.

Like the USA, one big deal is the lack of shower facilities. There, they use the rest rooms in the parks and don't have to hire toilets like Dignity Village, but there are no showers. So they pool their money to make regular trips to the public baths which are everywhere in Japan.

All the tent communities I visited were curious about Dignity Village - many had seen the web site and they all felt that it was important that homeless people everywhere are part of the solidarity movement (communicating and supporting each other and seeking for a more humane existence, including housing rights). From visiting them, it is obvious that, like here, there are countless individuals and many small organizations (businesses, some churches, not a lot) that help and do some good work with homeless people. But there isn't much in the way of supporter organizations like here and not the activists and there are so, so many tent groupings all over the parks, but they aren't organized and many only have a small number of tents grouped together and very few of these tent "communities" have supporter organizations. Given the Japanese homeless characteristics and their culture - manners, helping one another, taking pride in whatever job they do, however menial it might be - they are far more self-functioning without the need for more structure or formal organization or supporter organizations like here, where the homeless characteristics are far more challenging and the cities far less accepting of people that are in tents, let alone homeless. The negative to Japanese society (including the homeless) is that things are far more "homogenized" and they don't enjoy the richness of our society that has so much more diversity as compared to them (including diversity of ideas, backgrounds, experiences, "races"). They enjoy relative "harmony" but are victims of "one-think" and are more trapped by their culture, compared to here.

I liked the once-a-week peer counseling they had at Ougimachi and the fact that it was homeless led. My song was "Sukiyaki" and everyone held hands and sang it. Many had tears in their eyes afterwards and said they had never been closely together and held hands before (I also led them in a group massage). The Japanese do not readily, so it seems, feel comfortable with such intimacy.

As a footnote to this report, I might mention the Koreans. There are many Koreans in Japan and they have been brought over to Japan over the years (especially prior to WW II) as practically slaves. So, they have been greatly discriminated against. There are large Korean communities in Japan and they are almost entirely set aside from the larger city areas. How the Korean homeless cope with things, I don't know. However, in Korea, apparently, conditions for the homeless are very severe and much, much worse than Japan.

One more thing- they just loved the t-shirts from Dignity Village and loved the illustrations on the rear and the colors. There was one large homeless individual and I ended up taking my shirt off my back, which was extremely sweaty at that point, and giving it to him for he had been admiring it the entire evening. I regret not bringing a Pullman filled with shirts. I gave out some bees, which they seemed to like, also, and soon ran out of them. The Japanese love honey and prize it for cooking and their bee keepers are very meticulous.

From seeing and being with the homeless in Japan and then comparing them with Dignity Village, I came up with some recommendations to consider:

1) Jobs in any community to be done are often self-evident. Possibly, such work would be part of the Village's vision (a clean, safe, cooperative community, etc.). People could, using their own initiative, just do the obvious work and do it the best they can without being asked always or told to do it, knowing that they are contributing to the greater well-being of the community by doing so with the reward coming from one own's sense of pride and service. Obviously, this is a shift in our self-centered, chip-on-the-shoulder way of thinking that we have sometimes. At least, given our community's structure and jobs, possibly some of the time individuals could consider just doing what needs to be done more often.

2) Learn better manners. Obvious Japan has more people and there is a need for the "lubricant" of manners. Yet, good manners benefit everyone - and make for a nicer social environment. Possibly what "good manners" is could be discussed sometime, and even defined somewhat, to get some general agreement. Practicing good manners, even if it appears silly at times, might be beneficial for all and it would be nice, eventually, if good manners would come from the heart and be honest and sincere. Good manners help us realize that everyone, however screwed up, is doing the best they can at a given moment, given their experience, background and resources.

3) Learn and PRACTICE non-violent communication techniques. We have one organization (CFNVC) that some of you are acquainted with - why not see the videos and ASK them to come to the village for a workshop? Learn healthy ways of expressing disagreement. Learn to express strong anger, if need be, by going to a private spot (agreed upon tent) with a batucca or dummy and learn to shout if need be, where it isn't done in an abusive manner to another person), injuring them and the village harmony. Learn to express appreciation.

4) Keep "reaching out" and "networking" - consider every year doing an exchange with one or more other homeless groups. Continue positive goals and behaviors by helping others, dialogueing with the community at large, helping everyone to learn. I was impressed with the materials I was given on the Korean-Japanese exchange (street sleepers), ACHR - the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights - held in 2001 (see the enclosed materials I copied giving excerpts from this book). What they did is compile the findings and sharings of the exchange in the form of a written booklet, making it more possible for others to learn from the information. Possibly an exchange such as Santa Cruz might have been a better investment if such a compilation had been made. I'd suggest for future tent city summits that such an effort be made.

5) Have more fun. Celebrate your heroes. Celebrate each other. Celebrate successes. The Japanese do - often sitting together at afternoon tea and talking SOFTLY with one another or sharing sake and beers at night (not a recommendation for the village other than doing the social process). Bring in regular entertainment. Celebrate birthdays. Celebrate!

6) Peer counseling. This seems very worthwhile and we had a most satisfying, leader-led session at Nagai Park Tent Village. I suggest this strongly to the village. The sessions should be relatively small, limited to 10-12 people and there need to be ground rules (no judging and not talking while another has the floor and limiting time each person has to talk on given topics). All the topics don't have to be serious - just like talking about your favorite song and why it is meaningful to you, etc., as an example.

7) Listen more. Talk less. Practice this.

Well, there really was lots more. Being with the homeless in Japan, as here, was a privilege and I'm constantly reminded at how much talent there is all around us.

Thanks for listening.

Lee.